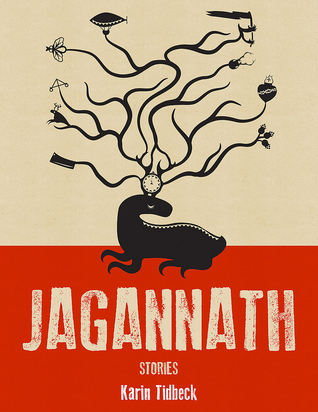

Swedish writer Karin Tidbeck’s first collection published in English, Jagannath, has recently been released by Cheeky Frawg, an imprint run by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer that focuses on translations and international fiction. The collection contains thirteen pieces of short fiction that range from whimsical to intensely discomfiting, all having a distinct touch of the surreal or the weird. Many of the pieces in question have never previously been published with English translations—though, of course, some were originally published in magazines like Weird Tales.

Jagannath has already received a great deal of word-of-mouth support from folks like China Mieville, Ursula K. Le Guin, Karen Lord, and Karen Joy Fowler, and has been reviewed quite favorably by Stefan Raets here on Tor.com. Tidbeck’s fiction is also acclaimed in her home country. As a fan of international fiction and someone interested in inclusivity in the speculative fiction community, I was particularly pleased to get my hands on this book, and it doesn’t disappoint.

These are odd stories—a touch of the weird, of the real world knocked sideways or rewritten in small but eerie ways, lingers throughout. This shade of the uncanny is what makes Tidbeck’s stories so engaging, no matter how short and often deceptively plain. Occasionally this is minor, as in “Miss Nyberg and I,” where the strangeness is merely the existence of a little plant creature. In other pieces, it is more intense and discomfiting, as in “Arvid Pekon”—where the phone bank that fakes phone calls for people needing services is contacted by Miss Sycorax, who apparently can rewrite reality with her words, up to and including erasing the protagonist from existence.

And as I say these things—“apparently,” “deceptively plain,” “uncanny”—I hint at what kept me coming back for more throughout the collection. There is a certain refusal in Tidbeck’s fiction: a refusal to offer clear answers, to explain, to justify. The weird is simply there, and the stories are concerned more with evocation and exploration of character than world-building or ruminating on an idea. Atmosphere trumps information; prose that provokes image and emotion trumps exposition.

In this way, many of the pieces in the collection are slight and understated, yet contain a certain depth of implication. “Herr Cederberg” is one of these stories that functions on an image—that of the titular character as a bumblebee—and transcends it in a brief blip of surrealism, a shining visual moment. However, this story is also one of the weaker of the book in contrast to the more evocative and developed pieces; sometimes the image is lovely, but doesn’t quite haunt. Of course, the majority of these stories do haunt. The titular story of the collection, in particular, is full of vaguely terrifying imagery and a conclusion that will leave many readers distinctly uncomfortable—though it is a “happy” ending, of sorts.

On a thematic note, there are also many stories that deal with gender and, indirectly, patriarchy. A feminist politics seems to inform the anger and the horrible things that happen in pieces like “Beatrice” and “Rebecka.” While these stories are, admittedly, about the bad things that happen, they are also clearly indictments on their own terms of otherwise sympathetic characters caught up in destructive social systems. The woman who tortures her friend until the now-incarnate male God kills her in retribution in “Rebecka” has been tormented beyond repair by a patriarchal system of values; she may have done something monstrous, but it is not necessarily her fault.

And, one last thing: I also find Tidbeck’s shifting back and forth between English and Swedish publications delightful and intriguing. It’s notable that she writes in Swedish and English both, and does not employ translators. Her English prose is particularly engrossing, leaving me curious about the Swedish originals and/or translations. I do wish I could read them, especially after finishing this book.

As a whole, Jagannath comes together well via the combination of its separate stories: their strangeness, their liminal and fantastical nature, their implications—all of these aspects merge and mesh to create an intriguing reading experience. I’m deeply glad to have Tidbeck’s voice available in the anglophone SF world, and I hope to see more from her. These stories have stuck with me; they are gently powerful, eerie, and provocative. I recommend them.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.